Narrative accounts of funeral processions described women who sobbed, screamed and even writhed on the ground.

But even in this context, medieval Christian women’s behavior was often viewed as disruptive or dangerous. In late medieval Christian society, an important part of religious life was the ritual of communal mourning, where a community would publicly mourn someone who died. Women particularly had their speech restricted during religious rituals. Taking their cue from Paul, medieval theologians encouraged husbands to monitor their wives and limit their public communication. For it is improper for a woman to speak in the church. But if they want to learn anything, they should ask their husbands at home. Women should keep silent in the churches, for they are not allowed to speak, but should be subordinate, as even the law says. As a justification, preachers and theologians cited 1 Corinthians 14:34, wherein Paul wrote: This concern for monitoring and regulating women’s speech had its roots in early Christian texts. Medieval culture did restrict women’s speech. How can this assertion be reconciled with the notion that medieval Christian culture sought to limit women’s speech, essentially silencing female voices in society and from historical records? “All the women of the township (should) control their tongues” Mary’s voice was regarded as provocative, and was often shaped to reflect or even satirize broader medieval social and religious concerns.

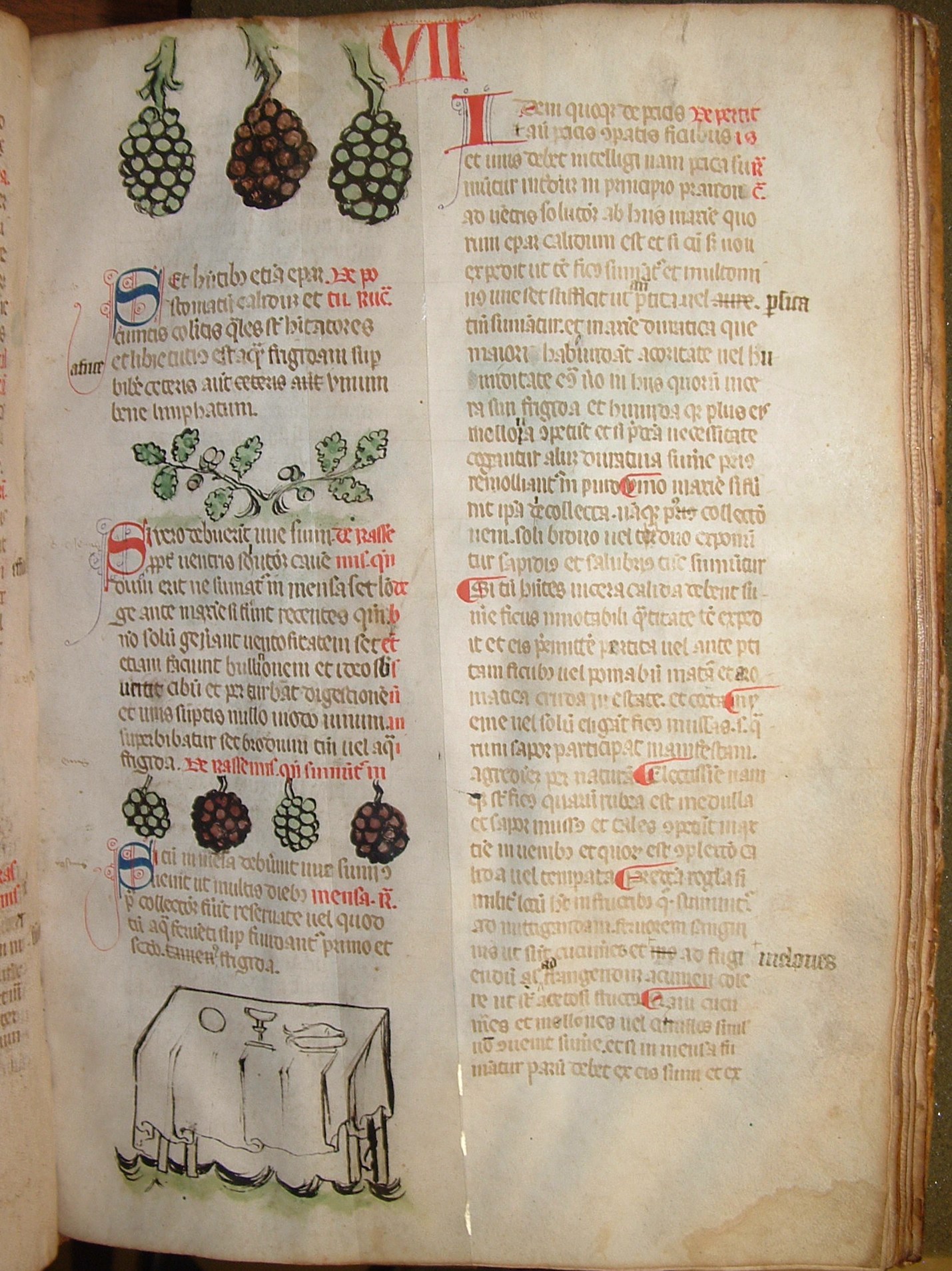

#Medieval illuminations transgender series#

Despite this, observations about Mary’s eloquent voice was frequent in a series of later medieval devotional sources. It struck me as a contradiction that the Virgin Mary-known as the Mother of God, Queen of Heaven, and a literal litany of other titles, and who inspired a rich profusion of religious devotion and culture-is only documented in the Bible speaking fewer than 200 words. Why then did late medieval authors and artists opt to depict her as a powerful woman who spoke “severely” to her supplicants, intoning, for example, “Thou hast provoked me to great anger?” Yet Mary, arguably the most famous woman in Western history, only spoke in the Bible on four occasions ( Luke 1:26-38, 1:46-56, 2:41-52, and John 2:1-11). A myriad of prayers, hymns, sermons, and other devotional practices imagined Mary speaking profusely to her supplicants. I was, in fact, very familiar with this image-my dissertation included numerous illustrations of Mary attacking the devil, as well as countless textual examples of Mary using her voice as a powerful instrument or even a weapon. Wasn’t the Mother of God praised for her serene nature? I received countless text messages asking, “Have you seen this?” People were shocked to see the Virgin Mary in such an assertive posture. My specialty being the veneration of the Virgin Mary, I was delighted when a manuscript illumination went viral in 2017 with the following introduction: “Please enjoy this image of the Virgin Mary punching the devil in the face.” Enjoy! Historiated Initial With The Virgin Mary Striking The Devil, In ‘The De Brailes Hours’ (c.

You can find the rest of the series here.Īs a medieval historian-arguably a pretty niche field-there is a singular thrill when a medieval image or news story captures the interest of a broader audience. This is Part 4 of The Public Medievalist‘s special series: Gender, Sexism, and the Middle Ages, by Vanessa Corcoran.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)